ABSTRACT

The owner of an all-women trekking tourism company in Nepal was interviewed regarding women’s empowerment in the tourist sector in Nepal. The research was undertaken in order to identify approaches to ameliorate poverty for women living in rural and remote Nepal. Throughout rural Nepal, women have traditionally been marginalized, undertaking home duties and childcare responsibilities; whilst simultaneously working in the fields (KC, 2012). Many impoverished and marginalized Nepali women have been empowered and ‘lifted out of poverty’ through the implementation of training and instruction programs designed to prepare them with skills to participate in the tourist industry in Nepal. The participant narrated stories of women moves from a lowly status in their home and village to levels of responsible positions in tourism and, in some cases, of running their own businesses. Opportunities for women now exist to train, practice and become workers and managers in the tourist industry. Training through female only owned companies is available to women who wish to engage with this approach. Avenues for self-employment, a steady income, positive gender role modelling and options in education are now open to these women (Satyal, 2000; Upadhyay, Pradhan&Grandon, 2011; Archarya&Halpenny, 2013). The research shows that through a grassroots approach to educating and informing women, avenues for self-improvement, self-advancement and growth through the development of local tourism are advancing the women, their villages and the country. But, as Nepal is still an emerging economy, there is a long way to go.

Keywords: Nepal, gender, tourism, grounded theory, poverty, and women

INTRODUCTION

Throughout rural areas in Nepal, women folk have customarily been disregarded; assuming familial obligations and child minding tasks at the same time as toiling in rural spheres (KC, 2012). Tourism to Nepal commenced in the 1950s subsequent to the opening up of the kingdom to the West by the traditional rulers (East, Luger, & Inmann, 1998; Satyal, 2000; Upadhyay, Pradhan, &Grandon, 2011). The onset of females contribution in Nepali tourism is coupled to their primary situation in the trekking business. Opening in 1994, the Three Sisters Adventure Trekking Company, created and operated by three sisters, Lucky, Diki and Nicki Chhetri, turned out to be inseparable from innovative trends in tourism for women folk in rural and remote Nepal. The Three Sisters are promoters and visionaries among Nepali women and have struggled tirelessly in the ensuing years to verify the perception that operating in tourism is a beneficial vocation(Jackson, 2010) for women. Consequently, they have trained more than 600 women, aged 18-49 years, who come from different areas of the country (Upadhyay et al., 2011, p. 84). This paper offers awareness into the community innovation of the Three Sisters and their influence regarding ameliorating poverty for village women in Nepal.

BACKGROUND

Nepal is a small, land locked nation-stated joined by India on its east, west and southern sides and China (the Autonomous Region of Tibet) in the north (Baral, Baral, & Morgan, 2004; Faye, McArthur, Sachs, & Snow, 2004; Shrestha & Aryal, 2011). The zone along the northern border of Nepal is the location of eight of the ten most elevated mountain sinter nationally, including Mount Everest (8848m), and is also home to several glaciers and glacial fjords (Shrestha &Aryal, 2011).

When bearing in mind Nepal service businesses, tourism is the leading international exchange supporter, as well as including an extensive portion of the country GDP and affording an assortment of employment possibilities. Thirty years ago, the extent of tourism in Nepal was moderately minor, but in the 1990s the size of worldwide tourist occurrences multiplied twice, creating an ensuing escalation in fiscal conditions and tourism substructure; predominantly lodging facilities. Tourism has benefited from various monetary changes introduced by the Nepali government from 1991, integrating restructured financing procedures and the denationalization of national trade (Baral etal, 2004). Nevertheless, while Nepal is a particularly well-off place in terms of the capacity proffered because of the advance in environment-centered and ethnic tourism commodities (Agarwal&Upadhyay, 2006), profoundly imbedded long-established patriarchal principles and socially constructed gender attitudes make it problematic for Nepali women, predominantly in remote and rural localities, to move in to and thrive in the tourism sphere (Flacke-Neudorfer, 2007).

Conditions for women who are likely to engage with tourism in Nepal

Community and locality-based tourism in Nepal is perceived as a road forward for womenfolk who find it challenging to gain entry to fiscal, scholastic, well-being and other opportunities in rural and remote districts. Advancement organisations have accentuated their conviction that women should be in corporate in to all factors of tourism and broader commercial undertakings, accordingly providing women with the likelihood of adopting managerial proficiency and thus attain more comprehensive acknowledgement within their communities (Scheyvens, 2000). Still, literacy levels of Nepali females continue to reveal the consequence of the task confronting women when looking to connect with the tourism industry. Literacy percentages(outlined as being the proportion of individuals aged 15 and above who can read and write) for the overall populace of Nepal is about 63.9%.On the other hand, literacy for men is about three quarters of the people(76.4%) whereas only just over 50% of the female inhabitants are literate (53.1%) (Central Intelligence Agency [CIA], 2016).

Several transnational, management and community groups have been concentrating on females advancement and emancipation in Nepal over the last 20-30 years. For instance, schemes such as the Small Farmer Development Project, Production Credit for Rural Women, Micro-credit Project and additional concentrated finance packages have been instigated in an effort to diminish women’s hardship (Upadhyay etal, 2011).Nonetheless, in spite of these attempts, Nepali women’s involvement in the socio-economic progress of the nation, and in tourism specifically, continue to be restricted.

Maoist insurgency created dislocated and lost families

The Maoist uprising, also called the 10 year war, or the peoples war (Baral&Heinen, 2006) commenced on February 13, 1996 with supporters of the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist (CPN-M), striking a police bureau at Halleri in the Rolpa district of Western Nepal. The disturbance in the Rolpa and Rukum districts has been attributed to many circumstances, including the privation and pervasive lack of progress of the locality, historic denigration in opposition to the authorities (for vetoing the cultivating of hashish in the 1970s, and the repression of CPN-M militants throughout 1994, as well asotherdisputes), and an instituted introduction of Communist activities in the locality (Gersony, 2003). From 1996 to 2006, the ‘People’s War’ broadened to almost all of districts in Nepal, with 73 out of 75 districts detailing casualties in 2004. The Maoists carried out repeated incursion sonar my strongholds, police bases, and village development committee structures (VDCs) and money depositories (Do &Iyer, 2006; Murshed& Gates, 2005).

Foregoing the Maoist unrest, women contribution to the political domain was exceptionally constrained (Upreti, 2009). The uprising convinced a size able sum of Nepali women into adopting armaments. Conversely, in a peculiarly equivalent occurrence to womenfolk post World War II, healing as been problematic for many female ex-fighters. They had to retrace their steps into the same male-controlled and obstructive social and cultural configurations that they had struggled to trans form. A number of the women had inter-caste or inter-ethnic marriages and as soon as they exited the comparatively democratic atmosphere of the insurrection, they encountered amplified and deepened prejudice from their districts that persisted stringently and separated them along caste-basedline ages. Yet, as many females had understood how to organise and became informed of their civil rights, it could be claimed that this has led to a remarkable escalation in females advancements and direct action concerning women concerns in a fundamentally male-controlled society (Bhandari, 2014).

POVERTY AMELIORATION OF WOMEN IN RURAL NEPAL

Privation is deeply embedded (Chand, 2000, p. 154) in Nepali villages and becomes even more problematic in isolated and remote areas. The development of tourism in wilderness areas affords noteworthy capacity for improving work opportunities and both conventional and unofficial prospects for small business expansion (Cleverdon, 2001). These possibilities empower local citizens to join in and gain from tourists who are attracted to wilderness, environment-centered encounters. Even though Nepali women have been, and carry on being, a meaningful protagonist in the advancement of Nepal, their persistent subservience has disguised their impact in their districts (Gurung, 2004). Even taking into consideration constrained assessment-making authority, limitations on movement, absence of influence over possessions and property, and diminished admittance to guidance and assets, females involvement in the expansion of tourism in their isolated villages has indicated both affirmative and adverse effects.

As with all emerging economies, the prospects for the tourism trade in Nepal is impaired to a large extent by a substantial number of issues. For instance, there is a considerable scarcity of resources and advancement assistance for isolated districts in general. Tourism is remarkably vulnerable to commercial, ecological and socio-political procedures which clearly shape global travelers motivation to take a trip (United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women [UN Women], 2011). In 2015 for instance, Nepal was pounded by a destructive earthquake in April and again with after-effects in May (Paris, 2015). As an obvious outcome of the catastrophe, tourist numbers tumbled and this has persisted with long-lasting consequences. While most resorts and guesthouses in reality were untouched by the earthquake, Euromon it or International (Kocheri, 2015) projected that tourists going to Nepal for vacation, would only start to return by the end of July that year. The Nepali government was also arranging extensive publicity promotions in India and China to persuade these tourists to come back and many of the tourist trails which had under gone nominal devastation were predicted to activate tourism activities once more by September. Despite that, by the conclusion of that year, tourist influxes were envisaged to get to only close to 70% of the customary numbers (Kocheri, 2015). Underprivileged populations in provincial and isolated locales may be acutely susceptible to these abrupt slumps in tourism requirements (UN Women, 2011).

Transformation of women in Nepal through Social Entrepreneurship

Bhushal (2008, p. 142) has suggested that, for the overall development of a society and nation, women participation is a must. But unfortunately women of our country mostly spend their time doing household activities and also involving in agricultural fields. Due to which education and knowledge acquirement is difficult. Daughters are referred as product going to others house and are refused to acquire education. Yet, by way of their own robustness and resolve, social entrepreneurship deliversa method through which Nepali females have seized options that have for merlybeen forbidden to them. The base of entrepreneurship is that it represents a special, innate ability to sense and act on opportunity, combining out-of-the-box thinking with a unique brand of determination to create or bring about something new to the world” (Martin & Osberg, 2007, p. 30). For the socially focused entrepreneur this ‘out-of-the-box thinking is merged with looking to acquire value in the form of large-scale, transformational benefit that accrues either to a significant segment of society or to society at large (Martin &Osberg, 2007, pp. 34-35).

At one time, females occupied in this are aware more disposed towards domestic responsibilities. The tendency has altered with many who have emerged as entrepreneurs, guesthouse proprietors, tour leaders and porters (KC, 2012). There are also noteworthy prospects for females to contribute to the creation and retailing of souvenirs through the expansion in women collectives and initiatives (see for example the Sabhung Women Micro enterprise Cooperative (Namlo International, 2016) among many others). Even as it is also tremendously problematic to guarantee that women have some direction over, and participation with, the earnings resulting from tourism activities (Scheyvens, 2000), there are a mounting number of illustrations of women alliances using tourism returns for the profit of villages (Ateljevic et al., 2008).

METHODOLOGY

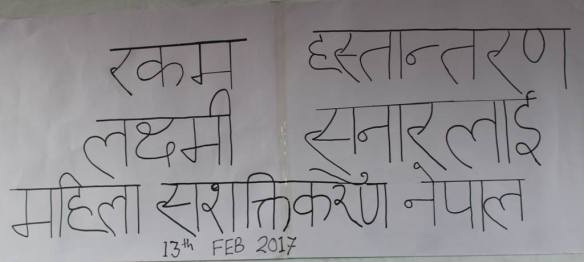

The investigation made use of a single case study (Yin, 2009) of one female who is appropriator and member of staff of a female only group that inspires women to seek out feasible and realistic work options in rural and remote Nepal. Single cases permit investigators to examine experiences in depth; to deliver rich narrative and interpretation (Darke, Shanks, & Broadbent, 1998; Walsham, 1995). The evaluation and results of the case study were guided by the use of a grounded theoretical approach (Charmaz, 2006). The in-depth interview was carried out at the premises of the Three Sisters Adventure Trekking agency, situated in Pokhara, Nepal. The participant is a Director of Empowering Women Nepal (EWN), a Nepali Non-Government Organisation (NGO), administered by and for women. The Three Sisters Adventure Trekking agency is an auxiliary of EWN.

Grounded theory is a qualitative inquiry methodology where the evolving theory is grounded in the data (Douglas, 2003). The constant comparative technique is used with the data, where the narratives of the interviewee are contrasted long side each other to distinguish comparable themes of significance contained by the data (Framm, 2013). Data is scrutinised, filtered, ranked and studied to uncover related themes and classifications. Once these categories are ascertained, data is additionally condensed to generate concrete perceptions which are then used as focal classification headings (Bulawa, 2014) for the building of a strong grounded theory that has transpired from the data (Charmaz, 2006). The main classifications and ideas that arose from the data were applied as the principal sub-headings for the Findings and Discussion segments of this paper (Fereday& Muir-Cochrane, 2006). This project is the foundation for additional inquiry into the field of women; work, health, tourism and transformation (see Radel& Hillman, 2013).

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The study has led us to pinpoint the subsequent main ideas and classifications that developed from the data Empowering Women Nepal (EWN), rural and remote Nepali women and tourism, and tourism training for women. These main ideas were attained through a thorough grounded theory constant comparison management of the data and are considered below.

Empowering Women Nepal

The account of the Three Sisters Adventure Trekking, a small practical tourism business with a prevailing ethical concern, is an account of how one organisation responded to a professional specialty demand (solitary women travelers) and is presently supported by an increase of specialty progress in women adventure tourism (see Beezer, 1994). This remarkable illustration of making the most of advances in coaching and inspiring females has guaranteed the Three Sisters Adventure Trekking and EWN international esteem. The Three Sisters project as matured into a unique campaign structure in the midst of Nepal 700 plus recorded trekking outfits (Chhetri& Lama, 2013).

What we do in our Three Sisters Adventure Trekking company is a business, and mostly we are focusing for women, by women, mostly the women trekkers they come in our company, and we are providing services, female trekking guide, and assistance for visit by women. And, to make this possible, to produce women trekking guide, we have a training center called Empowering Women Nepal that is an NGO (Participant).

Despite the fact that the Three Sisters Adventure Trekking and EWN are directed by the same administrators and perform jointly to advance and incorporate women in adventure tourism, both the establishments have distinct objectives. EWN comprises academic and material proficiencies, and Three Sisters Adventure Trekking furnishes employment and commercial visions to EWN recruits (Chhetri& Lama, 2013).

You know, this is a great profession for them, so we can ahh, we can keep some training for them, know they can make money and they don’t have to leave their country [for remittance work overseas]. They are going in their own country, in their own place, you know, and so they can develop that. So, this is really, really genuine profession that we can introduce for women. There is economic empowerment, leadership, here is everything you know (Participant).

The empowerment approach, which is fundamental to an alternative development standpoint, distinguishes an impact on autonomous option creation for localities, community self-confidence, frank understanding and innovative communal schooling. The foundation for empowerment must be at the practical level, as community culture is most effortlessly ordered around provincial matters. The focal resolve of empowerment is to accomplish egalitarianism through transforming the groups, activities and links that have encouraged eddies crimination (Mahat, 2003). Known for its training aptitude, EWN spreads its resources to environmental tourism development programs such as SNV Netherlands Development Organisation, Norwegian Development Fund, and the Global Fund for Women, and further afield (Chhetri& Lama, 2013).

Rural and remote Nepali women and tourism

Studies about women involved in the tourism sphere worldwide accept that the variety of tourism work obtainable for rural women is chiefly unsophisticated, low-rewarding work such as housekeeping and cooking preparation, identified as a broadening of their traditional(free of charge) domestic tasks(UN Women, 2011). On top of their tourism activity engagement, women are compelled to keep up their marital tasks, with tourism increasing their extensive work burden. Furthermore, women working in household tourism concerns are regularly doing so without salaries, contributing an insignificant amount to their eventual liberation as contributors to domestic earnings and questioning the possibility of such schemes (Sherpa, 2007).

In Nepal we have a concept, people who live in the mountain areas are poor people; and so there is no other facilities [sic]. So, the people are living with little facilities, yeah? On those areas there would be a good tourism product. So far we are working since 1994 in tourism and we are working in the Annapurna area mostly. It is a very popular area and because we are in Pokhara, this is the gateway of Annapurna region. We are mostly working on this area, but we like to expand in other areas also (Participant).

The advance in women reputation through such labor indicates a fulfilling area for Nepal to establish gender egalitarianism in terms of vocation. While taking into consideration the gender demarcations still customary in Nepal, exactly how these women sustain their domestic obligations with their employment keeps on being discounted (Hillman &Radel, 2016; KC, 2012).

Tourism training for women

Foreign development groups have assisted Nepali women to enrich their self-confidence and become keenly engaged in tourism as a product of providing schooling and education for them (Gurung, 1995). Additionally, development groups have made evident their concept that women should be assimilated in all facets of their pursuits, accordingly extending women the possibility to progress leadership abilities and attain far-reaching acknowledgement for their regions (Hillman &Radel, 2016; Scheyvens, 2000).

So we can train more women and introduce more women in tourism, because tourism is service oriented, it’s a service and women can also – because before the women were in the service industry and when the money comes, women are always behind. So, this is totally, I think, for women, and it’s supposed to be. So, we can, we can encourage women with this one. And also, we like to introduce in other developing countries; like in Africa, or South America and all Asian countries, that all women can also do the work in tourism (Participant).

Scholastic session sat the Three Sisters are meticulously devised. The purpose and goals of the syllabus are given in many components of instruction. This is because the Three Sisters is not a basic educational syllabus. It decisively educates females to practically work in adventure trekking and fosters leadership abilities. Women identified for this curriculum demonstrate a passion for independence and knowledge in this arena. The women typically possess vital leadership aptitude, which is sustained through the teaching, education and anticipated future employment (Jackson, 2010, p. 89).

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

In the course of the research, it became apparent that there were a range of obstacles for many women in rural and remote Nepal preventing them from moving into positions of reliable and autonomous earners through encounters with the tourism industry (Wilkinson & Pratiwi, 1995). These obstacles are problematic to surmount in a gender influenced patriarchal culture, like Nepal (Swain, 1995). The revolution in women significance through such occupation suggests a solid platform upon which Nepal can establish gender parity in terms of occupation. At the same time as hallowing for the gender classifications still widespread in Nepal, how these women sustain their household commitments with their work continues to be discounted(KC, 2012).

The travel sector in Nepal has become one of the chief resources adding to the country GDP by means of foreign exchange labourers and employment for women. This sphere supplies employment for 200,000 persons directly and approximately 1.2 million individuals incidentally (Upreti, Sharma, Pyakuryal, &Ghimire, 2010). Before this, women with work in this sector were more prone to be occupied in domestic type duties. This has altered of late. Numbers of young women have become business individuals, guesthouse owners, tour directors and porters. The upturn of women esteem through these types of vocations presents an advanced position for Nepal by producing gender justice through work. In considering the gender groupings still wide spreading Nepal, how these women even out their domestic duties with their work, is on the whole unacknowledged. Theories of gender discrimination emphasis that female situations in most circumstances are dissimilar from means owing to their treatment as unsatisfactory and second class citizens (Lengermann & Niebrugge-Brantley, 2000, p. 462). The importance of women in the tourist domain has been established.Still, for Nepal expansion and continuing sustainability, many more females need to be provided with the assistance and preparation to function as tour and trekking guides, homestay and lodging entrepreneurs, and tourism operators; along with opportunities to embrace comprehensive economic, organisational and social participation involvement.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Acharya, B., &Halpenny, E. (2013). Homestays as an Alternative Tourism Product for Sustainable Community Development: A Case Study of Women-Managed Tourism Product in Rural Nepal. Tourism Planning & Development, 10(4), 367-387. doi:10.1080/21568316.2013.779313

Agarwal, M. K., &Upadhyay, R. P. (2006).Tourism and economic development in Nepal.New Delhi: Northern Book Centre.

Ateljevic, I., Ampumuza, C., van der Heijden, F., Hendriks, N., Klunder, R., Mazurek, J., . . . van Rumpt, I. (2008). Women empowerment through tourism. Retrieved from The Netherlands:

http://videa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Women-empowerment-through-Ecotourism.pdf

Baral, A., Baral, S., & Morgan, N. (2004). Marketing Nepal in an uncertain climate: Confronting perceptions or risk and insecurity. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10(2), 186-192.

Baral, N. &Heinen, J. (2006).The Maoist people’s war and conservation in Nepal. Politics and the Life Sciences, 24(1-2), 2-11.

Beezer, A. (1994). Women and ‘Adventure Travel’ Tourism. New Formations, 1990/1991, 119-130.

Bhandari, C. (2014). The Reintegration of Ex-Maoist Combatants back into Nepali Society Paper presented at the 13th Annual Symposium of the Centre for Poverty Analysis, Kathmandu.

Bhushal, S. (2008). Educational and socio-cultural status of Nepali women. Himalayan Journal of Sociology & Anthropology, III, 139-147.

Bulawa, P. (2014). Adapting Grounded Theory in Qualitative Research: Reflections from Personal Experience. International Research in Education, 2(1), 145-168.

Central Intelligence Agency [CIA]. (2016). The world factbook – South Asia: Nepal. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/np.html

Chand, D. (2000). Nepal’s tourism – Uncensored facts. Varanasi, India: Pilgrims Publishing.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Chhetri, L., & Lama, W. (2013).Breaking Gender Barriers: A Market-Based Approach to Women’s Empowerment through Tourism.In K. Bricker, R. Black, & S. Cottrell (Eds.), Sustainable Tourism and the Millennium Development Goals (pp. 115-126). Burlington, MA, USA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Cleverdon, R. (2001). Introduction: Fair trade in tourism – Applications and experience. International Journal of Tourism Research, 3, 347-349. doi:10.1002/jtr.352

Darke, P., Shanks, G., & Broadbent, M. (1998).Successfully completing case study research: combining rigour, relevance and pragmatism. Information Systems Journal, 8, 273-289.

Do, Q.-T., &Iyer, L. (2006). An Empirical Analysis of Civil Conflict in Nepal. Institute of

Governmental Studies, UC Berkeley, 1-19 plus Appendices.

Douglas, D. (2003). Inductive theory generation: A grounded approach to business inquiry. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 2(1), 47-54. Retrieved from

East, P., Luger, K., &Inmann, K. (1998). Sustainability in Mountain Tourism: Perspectives for the Himalayan Countries New Delhi: Innsbruck.

Faye, M., McArthur, J., Sachs, J., & Snow, T. (2004).The Challenges Facing Landlocked Developing Countries. Journal of Human Development, 5(1), 31-68.

Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006).Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80-92.

Flacke-Neudorfer, C. (2007). Tourism, gender and development in the third world: A case study from northern Laos. Tourism and Hospitality Planning& Development, 4(2), 135-147. doi:10.1080/14790530701554173

Framm, S. (2013).The Constant Comparative Analysis Method Outside of Grounded Theory. The Qualitative Report, 18(1), 1-25.

Gersony, R. (2003). Sowing the wind: History and dynamics of the Maoist revolt in Nepal’s RaptiHills. Retrieved from

Gurung, D. (1995). Tourism and gender, impact and implementation of tourism in Nepalese women. Retrieved from Kathmandu

Gurung, M. (2004).Women and development in the third world – A case study from Ghandruk, Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal: World Wildlife Fund – Nepal Program Office.

Hillman, W., &Radel, K. (2016). ‘It’s not mass tourism’: Using tourism to ameliorate poverty for village women in rural Nepal. Paper presented at the CAUTHE 2016: The Changing Landscape of Tourism and Hospitality: The Impact of Emerging Markets and Emerging Destinations, Sydney.

Jackson, M. (2010).Empowering Women of Nepal: An experience of empowerment in the land of the Himalaya.(MA), Prescott College, unpublished. Retrieved from http://gateway.proquest.com/openurl?url_ver=Z39.882004&res_dat=xri:pqdiss&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&rft_dat=xri:pqdiss:1475780 (1475780)

KC, S. (2012). Roles and challenges of women in tourism sector of western Nepal: A micro-ethnographic study. Nepal Tourism and Development Review, 2, 32-59.

Kocheri, S. (2015). Nepal’s Tourism Shaken by Natural Calamity. Euromonitor International – News & Resources. Retrieved from Euro monitor International – News & Resources website: http://blog.euromonitor.com/2015/07/nepals-tourism-shaken-by-natural-calamity.html 17

Lengermann, M. P., &Niebrugge-Brantley, J. (2000).Contemporary feminist theory. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), Sociological theory (pp. 447-496): McGraw Hill International.

Mahat, I. (2003). Women’s Development in Nepal: The Myth of Empowerment. Praxis: The Fletcher Journal of International Development, 18, 67-72.

Martin, R. L., &Osberg, S. (2007). Social entrepreneurship: The case for definition. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Spring, 2007, 29-39.

Murshed, S., & Gates, S. (2005). Spatial-horizontal Inequality and the Maoist Insurgency in Nepal. Review of Development Economics, 9(1), 121-134.

Namlo International.(2016). Namlo International – Women’s Empowerment. Retrieved from

https://www.namlo.org/programs/womens-empowerment/

Paris, N. (Producer). (2015). Nepal prays for return of tourists after earthquakes. The Telegraph. Retrieved from

Radel, K.& Hillman, W. (2013). Not on vacation: Survival escapist as an agent of transformation. In Y. Reisinger (Ed.), Transformational Tourism. Oxfordshire, UK: CABI.

Satyal, Y. (2000). Tourism Monograph of Nepal. Delhi: Adroit Publisher.

Scheyvens, R. (2000). Promoting women’s empowerment through involvement in ecotourism:

Experiences from the Third World. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(3), 232-249.

Sherpa, Y. (2007). Mountain tourism: A boon or a bane? Impacts of tourism on Himalayan women Retrieved from http://lib.icimod.org/record/12953/files/1366.pdf

Shrestha, A., &Aryal, R. (2011).Climate change in Nepal and its impact on Himalayan glaciers.

Regional Environmental Change, 11(Suppl 1), S65-S77.

Swain, M. (1995).Gender in Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(2247-266).

United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women [UN Women]. (2011). The global report on women in tourism 2010 preliminary findings. Retrieved from New York: http://www2.unwto.org/sites/all/files/pdf/folleto_globarl_report.pdf

Upadhyay, R. P., Pradhan, H., &Grandon, R. (2011).Women in Nepalese tourism – Opportunities and challenges. Varanasi, India: Pilgrims Publishing.

Upreti, B. (2009). Nepal from War to Peace: Legacies of Past Hopes for the Future. New Delhi: Adroit Publishers.

Upreti, B. R., Sharma, S. R., Pyakuryal, K. N., &Ghimire, S. (Eds.). (2010). The remake of a state – Post-conflict challenges and state building in Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal: South Asia Regional Coordination Office of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research [NCCR North-South] and Human and Natural Resources Studies Centre [HNRSC].

Walsham, G. (1995). Interpretive case studies in IS research. Nature and Method. European Journal of Information Systems, 4, 74-81.

Wilkinson, P., &Pratiwi, W. (1995).Gender and tourism in an Indonesian village. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(2), 285-299.

Yin, R. (2009). Case study research: Design and Method (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.